Sand castles: Vero 25 years after Marriott

In the gray light of an overcast day, reflected off the steely waterfront into Jim Durbin’s glass-walled living room, the former Marriott hotel president’s brown eyes intensify under a suddenly furrowed brow.

Only a moment before, Durbin’s face showed the strain of the tumult from a quarter century ago, when he had been the engine behind a proposed Marriott Ocean Drive resort voted down by the Vero Beach City Council.

Now, a nascent rumor that a Marriott hotel may be coming to the Vero Beach island sets off the deal-making gears again.

Nursing an injured leg, he leans forward gingerly in his recliner, and puzzles over a mental Rolodex of possibilities: The hotel he knows they’ve had an eye on? A local hotel family with Marriott ties elsewhere?

He hasn’t heard a word of this himself; this is the first whisper, and it is not from local sources.

A Marriott beachside in Vero. It is a concept he still believes in deeply. Asked about the plan he spent three years developing, and that the Vero Beach City Council shot down 25 years ago next week, he responds in the present tense, “It is a very good idea.”

Jean Durbin prefers to put the past behind them. Though she makes no mention of it, it may revive painful memories beyond most people’s knowledge. This awful chapter played out as Durbin’s first wife was dying.

“I love the people here,” Jean Durbin says. “I don’t want to bring it up again.”

She urges her husband to resist rifling through an old briefcase full of papers, infused with emotion still, the tissue-thin renderings, the stamped documents, the handwritten letters pro and con. She is wary of rehashing the story. Decades after the controversy ended, when a columnist revisited the story a few years back, they still got angry calls in the night, she says.

But aren’t these notes the sentimental traces of her husband’s dream? “It wasn’t a dream,” she fires back. “It was a nightmare.”

They worked their fingers to the bone, she says, though she uses a stronger metaphor.

While Durbin, 84, was recuperating at a rehab center this summer, he met a woman who figured out who he was, and recalled the controversy in an instant.

“I’m against it!” she blurted out as if the whole thing were still at the brink of happening, and her input still essential.

History can only hint at what might have been if the vote in the middle of that October night in 1985, taken following a town hall meeting so packed that the crowd spilled outside of the high school auditorium, had gone differently.

Twenty-five years of tax revenue, an estimated 250 more jobs, thousands of affluent executives lured by business conferences given the chance to discover Vero, and remembering it when it came time to retire.

No hotel in Vero Beach proper comes close to offering the meeting space of that proposed Marriott; the largest is not even half its size. It is the closest the Vero barrier island has come to having a brand-name luxury resort not just on its shores, but in its midst.

As the sluggish summer months roll into the doldrums of autumn, beachside shopkeepers almost startle at the sight of a customer; a quarter of a century ago, the proposed 260-bed hotel was promoted as a year-round draw.

And it was not the work of outsiders. Jim Durbin and his family had been visiting since the 1960s.

Durbin, who grew up in a hotel family in Indiana, joining Marriott in its earliest days after graduating from the University of Notre Dame, had family ties here. He is the nephew of Carroll Otto, who was instrumental in building Riverside Theatre. There is little doubt he understands as well as anyone the essential character of Vero Beach.

“I just went and had my hair cut at the same barber shop I’ve been going since 1964,” he laughs, running a hand over his smooth pate. “I told them they were taking a little too much off.”

When Jim Durbin semi-retired here, and couldn’t resist doing more of what he does best – build hotels – he never expected to find opportunity in his own backyard.

When a group of oceanfront property owners came to him with a proposal, they all believed there would be strong support for their idea. Everyone knew the caliber of Marriott resorts, and Durbin vowed to make this one world-class. When it was all over, he would go on to build 14 more hotels, starting his own management company, now run by his son.

“Durbin was really a visionary,” says attorney Michael O’Haire, who represented Durbin and the landowners involved. “He’s the one who said, when he was approached by the oceanfront landowners, ‘Well, we’re going to need more land for this.’ And they went out and got it.”

In all, the landowners and Durbin optioned 14 properties, not just those on ocean, but on the block to the west of Ocean Drive. In his plan, Ocean Drive would have been rerouted up Date Palm to Eagle, and then north to Greytwig, where it would swing back down to the boardwalk. All the houses in the western block would have been razed for the Marriott parking garage.

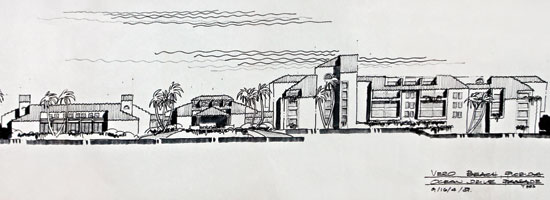

This was Durbin’s vision: on 16 acres, barely visible behind a high heavily landscaped berm, the Marriott would present itself as a low-slung, tennis-oriented resort equipped with a ballroom and large meeting rooms, and a two-tiered parking garage.

Apart from a central tower that rose five stories, the rest of the resort had a profile of only three floors – lower than Durbin’s living room ceiling, he is quick to point out. That would have reassured many residents who remained aghast that the 12-story Village Spires condominiums just south of the site, seemed to have slipped in to Central Beach like cat burglars, well before the wall of high rises on the St. Lucie County end of the island.

“Those two high rises caused such a furor that I think this would have felt like more of the same,” says Susan Schuyler Smith, a renowned interior designer who today sits on the city’s architectural review committee and previously served on a similar board in West Palm Beach.

Five years after the controversy, she bought a home in the very block that would have become the Marriott parking lot. Today, she tends to side with opponents of the Marriott.

“People felt it would have destroyed the whole nature of the Central Beach area.”

And while planners and council members may have taken their eye off the seismograph when the Spires were built, Durbin and his cohorts may have underestimated the neighborhood’s vow of vigilance, attuned to any and all aftershocks. With the Marriott proposal, the island trembled again.

Metaphorical earthquakes aside, another force of nature was at work in the debate – erosion.

Of the properties in question along north Ocean Drive’s Block 19, several were heavily damaged or had been washed away during 1979’s Hurricane David and a violent 1984 Thanksgiving Day storm that made the national news. Permits for sea walls were virtually unheard of, and while beach renourishment was an expensive option at public beaches, private oceanfront residences stood virtually no chance of recovering their lost sand.

For the owners in Block 19, the only entity that would lavish money on a crumbling shoreline was a corporation like Marriott. Trying to sell their land while it was zoned for residential seemed a hopeless folly; any homes built there would be castles in the sand.

At the public hearing on the rezoning request that could have changed the land from residential to “tourist commercial” on the comprehensive land use plan, a group called Save Our Shores spoke out in favor of rezoning, saying Marriott had pledged to do whatever was necessary to preserve the beaches going forward.

Chari Boye Elarbee said it best. An oceanfront landowner desperate to sell, and at the same time, a well-liked civic activist, Elarbee told the audience at the public hearing of living here all her life, and of how the yard where she and her brother Bill played was like “a football field.”

She described the horror of waking up one morning and finding her home falling into the ocean. She said the city had been all for changing the zoning back in 1981 when she first approached them, and that they had told her to come back with a development plan. She sought out the Marriott—not the other way around, as if that would seem less predatory to residents, one assumes.

Only a handful of houses sat on the property in question, the last remaining stretch of undeveloped oceanfront land in Vero north of Old Riomar. It took Chari Boye Elarbee and all her powers of persuasion to convince her neighbors to give Jim Durbin options on not only the oceanfront land, but lots and houses on the block bounded by Ocean, Date Palm and Eagle Drive.

Callie Corey, owner of Corey’s Pharmacy, was one of the last hold-outs. “We dug our heels in because I didn’t really want to give up my house, but when we saw everybody else was for it, then we signed on too.”

Meanwhile, opposition was also consolidating. Six-time mayor Jay Smith calls himself “instrumental” in fighting the required rezoning. “They wanted the city to abandon the Ocean Drive right-of-way from Date Palm north, and they would get nothing. With the easements, that was upwards of two acres. That’s a nice freebie, isn’t it?” declares Smith, 83, now in a wheelchair in declining health , still living on Eugenia Road, along with his wife.

From the other end of the island, similarly confined after shattering a leg this summer, Durbin shakes his head, straining to comprehend Smith’s past concern; nothing would have been had for free, he says calmly. “We would have paid for everything.”

Smith was not mayor at the time of the Marriott vote. But he points out he kept a hand on the controls of local growth – or the lack of it. “Most of the time that I was not on the council, which was 12 years, I was on the planning and zoning board,” he says. “And for most of those 10 years, I was chairman.”

Smith says economics are the reason he opposed the plan. “The facility would have required more services than straight residential,” he says. But there was also concern for a certain village esthetic for the island’s central district. “The feeling was that we had kept some oceanfront property as residential on South Ocean Drive and Riomar, and we wanted to keep a balance in the north.”

In fact, the planning and zoning board gave its approval to the project, albeit by a split vote. It wasn’t until the night of the required public hearing that the City Council, which by Durbin’s count, supported the project four to one, suddenly reversed course.

The biggest force behind the plan was also the most unassuming: Jim Durbin himself.

“It was supposed to be his hotel, the flagship of the Marriott, even though he was no longer president. He was so deeply involved and he wanted to make it something very, very special. I thought it would have been absolutely spectacular,” says Will Siebert, one of the property owners willing to sell their land. “If you’d told me there was a proposal for four small chain hotels, I wouldn’t have supported it. But this would have been a tremendous plus.”

Siebert’s superlatives found their counterparts in protest. A group calling itself Citizens Against Urban Tampering In Our Neighborhood, or C.A.U.T.I.O.N., put out a pamphlet claiming cars would “roar through the neighborhood with wild abandon,” and that “noise levels will be savagely elevated.”

The flier warned of brightly-lit tennis courts, and worse, the din. “Have you ever heard tennis balls being struck back and forth, hour after hour? It will drive most people wild.”

It spared no hatred for the gentlemanly Durbin, alleging his obvious “contempt” for his fellow citizens of Vero, and suggesting he could face a similar outrage in his own neighborhood, the Moorings: An oceanfront slaughterhouse, the flier suggested.

The proponents lauded the Marriott brand, proud that Durbin had chosen Vero Beach to build such a classy resort. They lamented the lack of any fine hotel for even a small convention or conference center – at the time, there was not much more than the less-than-corporate Driftwood Inn and the Holiday Inn.

By comparison, the Marriott, with its proposed Olympic sized pool, two bars, 16 tennis courts, porte-cochere and ballroom, struck supporters as fitting in perfectly with Vero’s step-above self-concept.

But opponents unleashed a torrent of concerns, from the rational – density, hurricane evacuation, traffic, even sea turtle nesting – to the highly irrational.

“Some woman said there were going to be orgies on the double beds,” recalls Durbin in a moment of mirth. “There was talk of ladies of the night on Ocean Drive.”

The more pragmatic arguments were left to former mayor Smith and others concerned with fiscal trade-offs. “Relocating utilities around the site would be totally at the expense of the city, as high as $1 million by my estimate,” Smith says.

There were other numbers that mattered as well, a more fundamental formula. “The comprehensive land use plan predicted 80 percent residential and all other zoning 20 percent. This would have changed the math of Vero Beach forever,” says Smith.

The Marriott was “imagining itself right into a prime residential area in the north Central Beach area,” including Smith’s own street, Eugenia, which he says would have led right into the Marriott’s parking garage. And there would no doubt have been more zoning changes down the road, he predicted. “There were so many unknowns out into the future that I had to oppose it,” he says.

Other Vero powerhouses took the opposite view. The man who introduced Durbin well into the public hearing that October night in 1985 was none other than the late Bill Whyte, one of Vero’s most influential residents, a former U.S. Steel executive and confidant of Gerald Ford’s, who, after moving to Vero Beach, had raised millions for the Indian River Hospital Foundation.

A force in local Republican politics, and a pioneer in public relations, Whyte, who died last April, was just the man to introduce the soft-spoken Durbin to the anxious crowd, so large, the meeting had to be moved to the Vero Beach High School auditorium. Even then, more than a hundred had to stand outside, Siebert recalls.

Durbin proudly showed slides of the hotels he had built – as first president of Marriott, he oversaw the chain’s growth from four hotels to 220, with his last project in Cairo, Egypt. He explained how projects are financed, and protected against bad management.

“Jim Durbin had a tremendous influence on my decision,” says then-council member Gary Parris, the lone pro-Marriott stalwart on the City Council. “He was a class guy. I had sat down with him for many hours. I would call him back, drill him and call him back again. Of course, he had everything to gain. But he was willing to make changes if we asked him to. He did everything he possibly could. He was trying to do a project that would bring dignity to this community. We are very fortunate to have him here still.”

If Parris was feeling relaxed at Durbin’s presentation when the Council took a break around 9 p.m., he should have fastened his seat belt when it reconvened, for a veritable verbal nor’easter hit Elarbee, Siebert and the rest, eroding all their hard work in a few stormy hours.

Parris, who played tight end for seven years in the NFL after graduating from Vero Beach High School and FSU, put it this way: “I’d rather face Mean Joe Greene than have to face the kind of scrutiny those people gave us, when you’re just trying to do your best.”

John Morrison spoke on behalf of the Vero Beach Civic Association, big money opponents of the project, who urged that a park be built on the properties. Norman Badenhop spoke representing the Taxpayer Association. Ellie Vanos spoke out in opposition, as conservation chairman for the Pelican Island Audubon Society.

Not that proponents weren’t heard as well. They included representatives from the Chamber of Commerce and the Treasure Coast Job Training Center, from Piper Aircraft, from the Treasure Coast Builders Association and the county’s Economic Development Council. Builder David Croom spoke on behalf of the General Contractors Association.

When the City Council, nearing midnight, asked for a voice vote among the overflow crowd, Durbin and Seibert both thought the ayes had it. Even the opposition called it 50-50.

Of course, the only opinion that counted in the end was the Council’s itself.

“I knew all of these guys,” says Siebert. “I had talked to all of them individually and I knew it was going to be close.”

At midnight, Parris, the youngest on the Council, made a motion to accept the request for a zoning change. The motion died for lack of a second.

From there, things unraveled quickly, as various concerns – quality of life chief among them -- were voiced by increasingly cautious council members.

Then came the death knell. Mayor Bill Cochrane brought up a letter received from the Department of Community Affairs only four days earlier, expressing serious concerns over studies that questioned whether Vero’s roads and bridges were adequate to evacuate the island; only a month before, a hurricane along Florida’s west coast had resulted in what was then the largest evacuation in U.S. history.

The DCA’s letter, Cochrane told the hall, might make the whole discussion academic. It seemed to imply some monetary consequence if Vero Beach did not comply “responsibly” with a larger plan that took in the St. Lucie County end of the barrier island, known there as Hutchinson Island.

By then, no one was in the mood to parse words in what seemed like a threatening letter from a state authority. Not at a quarter past midnight.

A motion was made to deny the rezoning. It passed 4-1, with Gary Parris casting the lone vote in favor of the Marriott plan.

“If there had been a referendum, the community would have voted for it,” says Parris today. “I just couldn’t find anything that would allow me to vote against it.”

The fight wasn’t over.

Cars still sported bumper stickers, there were still signs stuck in yards. Full-page ads in the local newspaper, proudly clipped out by their respective sides, still hung from refrigerator doors. Letter-writing campaigns had generated stacks of mail, banged out on manual typewriters with corrections inked in, or written by hand. There is even a post card of pink flamingos in the pile at City Hall. Jim Durbin has another stack, and doubtless other key players received still more.

Congestion had been a chief concern of those resisting the resort. As it was, seasonal stop-and-go traffic along A1A and Beachland Boulevard was maddening enough. They were imagining another 260 carloads of tourists ogling the oak canopies in Riomar, or blowing through intersections with their big-city ways.

And it wasn’t just aggravation. There were safety concerns as well. Never mind that in Florida, tourist season would likely never coincide with hurricane season: the state needed to know that anyone on the island could get off in a hurry if they had to.

More importantly, at least to government officials, was compliance with local comprehensive plans. Only a year before the Marriott proposal was put before the city council, the state of Florida had passed a law revisiting the botched planning efforts of the previous decade, and now required that regional policy plans be submitted for approval by the legislature.

That law was followed by another enacted in 1985 that made local governments amend their plans to comply with state and regional plans; failure to do so would result in loss of state revenue-sharing and grant money controlled by the state government.

The body that oversaw that compliance was the Department of Community Affairs, the source of that letter that came up at the end of the public hearing.

A year later, in 1986, the Block 19 coalition of property owners went back to the City Council with a request for rezoning to higher density – without mention of the Marriott. Another public hearing was scheduled, this one at City Hall. This time, it was Mike McDaniels of the Department of Community Affairs who began the meeting, at Mayor Cochrane’s request.

McDaniels told the council that the request for rezoning to higher density than single-family homes was inconsistent with the Hutchinson Island Management Plan in that the Vero Beach traffic zone already had more traffic than the capacity of its roads and bridges in the event of an evacuation.

Then-city manager John Little seized on his objection. Would that mean that Vero might lose state funding, were it to approve the request against the recommendation of the DCA? Would there be sanctions?

McDaniels denied there would be such consequences. But planning director Walter Young would not take no for an answer. He had been given the clear impression, he told the council, that indeed, were they to approve the request, they could be in violation of the DCA’s recommendations and that sanctions could take the form of grant monies being denied to the city. According to the minutes from that 1986 hearing, Young thought that money could add up to $1 million.

It was then that City Council member Hoyt Howard spoke up. We shouldn’t be afraid of Tallahassee or any attorney either, for that matter. But, he said, it wasn’t right to make zoning changes just to please “a few people.”

He made a motion to deny the zoning change again. It passed unanimously.

And still another coda, this time in the courts.

On Dec. 7, 1988, Circuit Judge Paul Kanarek empanelled a jury to hear a civil case brought by Michael O’Haire on behalf of the widow Eve Siebert et al against the city of Vero Beach, asking the court to declare the city’s decision to deny the change in zoning invalid.

After four days of trial, just as the jury was considering its verdict, Judge Kanarek called a halt to deliberations to offer a directed verdict. Essentially, he ruled in the city’s favor, finding that the issue was “fairly debatable,” the legal standard of the day, that there was enough evidence for the city to believe that the DCA could make real trouble over the Hutchinson Island evacuation plan.

Today, the oceanfront lots are selling piecemeal, still zoned residential. Only one remains occupied by an owner from that era – Adele Clemens. She says a lot adjacent to hers just sold to a couple from Tampa.

Elarbee and Siebert sold to Jan Jelmby, a high-end builder who moved here from Sweden in 1984, and lives only a few blocks away. In 2001, his firm, Helmet House, began work on the first of five planned 11,000 square foot Italianate mansions – with seawalls. One has sold, another is listed for $8 million.

A decade would pass before the island would have another shot at hosting a world-class resort. This time though, Disney’s Vero Beach Resort had a much easier time of things. Once again O’Haire’s client, Disney was proposing its resort at a virtually untraveled end of the island, near Wabasso. Still, he wasn’t taking any chances.

“We did an end run,” says O’Haire, describing his successful strategy that go-around: He ordered up a zoning change that described the Disney plan to a “T.” It passed.Disney celebrates its 15th anniversary this week.